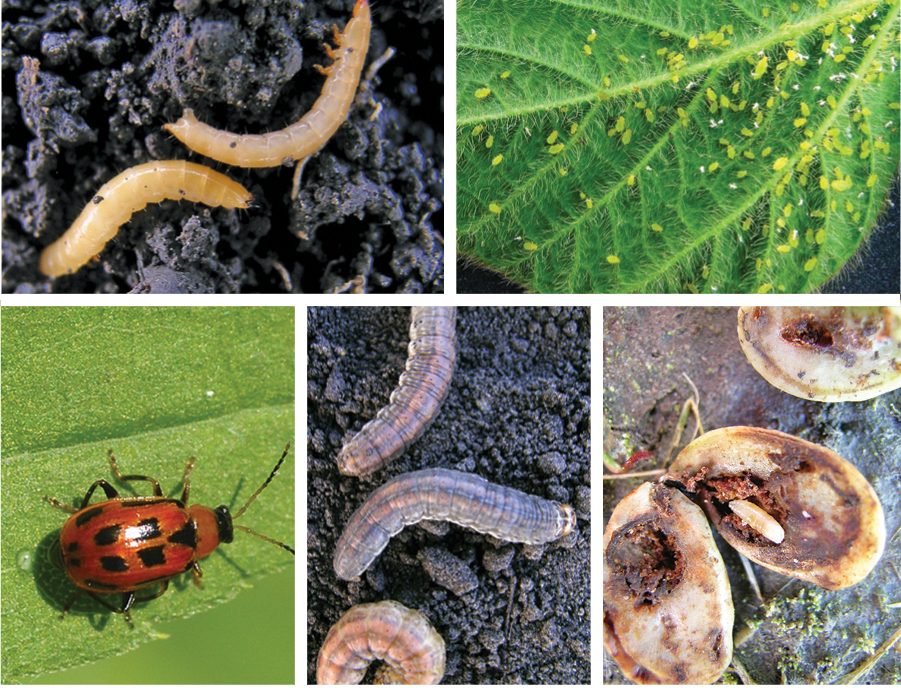

The following risk assessment was developed to help farmers and agronomists identify where seed treatments are most likely to be beneficial by describing the factors that influence soil insect populations and fungal pathogens. The targeted use of seed treatments supports an integrated pest management approach, which takes into consideration both economic and environmental factors.

For each soybean field, review the risk factors and considerations outlined in the table below to determine your risk of early-season insect pests. If your risk is low, consider ordering and planting fungicide-only, or bare seed.

In 2021, Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) released its review decisions on the neonicotinoid pesticides, thiamethoxam and imidacloprid. Use of imidacloprid (Stress Shield 600, Alias 240 SC, Sombrero 600FS) in pulse and soybean crops remains the same, with some label amendments for safe handling and disposal of treated seed. The maximum use rate for thiamethoxam (Cruiser 5FS) in soybean seed treatments has been reduced to 30 g.a.i/100 kg seed, which will cancel its use for wireworms.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR USING A FUNGICIDE-ONLY SEED TREATMENT:

- Fungicide seed treatment can help provide control over seedling and root rot pathogens in soybeans, including Rhizoctonia solani, Fusarium spp., Pythium spp., and Phytophthora sojae. It is important to remember that seed treatment can only provide protection for two to three weeks beginning at the time of planting (not emergence). These diseases can also cause issues later in the season if conditions are conducive for infection; therefore, seed treatment is not a complete solution.

- Fungicide seed treatment can be of greater benefit if there is a history of seedling disease or root rot, or if conditions are cool and wet at planting. Overall, planting into warm, well-drained soils at the proper depth (0.5–1.5 inches) will allow the plant to quickly emerge and have vigorous plant growth. A strong, healthy plant is better equipped to defend itself against disease if conditions become less than ideal later in the growing season.

- Crop rotation is important to reduce seedling disease and root rot from Phytophthora sojae (the causal agent of Phytophthora root rot in soybeans) because soybean is the only host plant. Other common pathogens that cause seedling disease and root rot (Fusarium spp.) have a wide host range.

For each soybean field, review the risk factors and considerations to determine your risk of seedling diseases and root rots. Prevention strategies include crop rotation and genetic resistance of soybean varieties (if available). It is important to remember that seed treatment is only effective until the very early V-stages.

It is difficult to distinguish root rot pathogens from one another. Shared symptoms include poor emergence and root development, yellowing, discoloured roots and lesions on the root or stem tissue near the soil line.

On-Farm Network Research Highlights

While there are proven scouting techniques and economic thresholds for several foliar pests, farmers have very few tools to estimate risk from soil-borne pests. As a result, seed treatments are frequently applied on a just-in-case basis with little knowledge of the risk soil-borne pests actually pose to a given crop. With the cost of common seed treatments ranging from $6–18/ac, optimizing the seed treatment decision would be a positive step toward profitable and sustainable soybean production.

Fourty-three On-Farm Network soybean field trials were established in Manitoba comparing treated versus untreated seed (2015 to 2019). Seed treatments consisted of either fungicide + insecticide or fungicide alone. The objective of these trials were to examine the decision to treat seed versus planting untreated seed when armed with minimal knowledge of the risk from soil-borne pests. Over the five years of this research, applying seed treatments as a form of self-insurance prevented yield loss 19% of the time. Positive yield responses occurred in 2015 and 2016.

There was no specific factor (seeding date, crop establishment, previous crop) that corresponded to the sites with a positive economic response. To view individual trial reports for these trials, visit manitobapulse.ca/on-farm-network.

At one trial in 2016 (2016-SST10), wet spring conditions led to excessive root rot and drown outs in the field, reducing plant stands. Under these challenging conditions, a yield response of 2.3 bu/ac was observed.

At one trial in 2016 (2016-SST10), wet spring conditions led to excessive root rot and drown outs in the field, reducing plant stands. Under these challenging conditions, a yield response of 2.3 bu/ac was observed.

The use of seed treatments should be evaluated on a field-by-field basis, considering the risk factors above that would warrant a seed treatment.